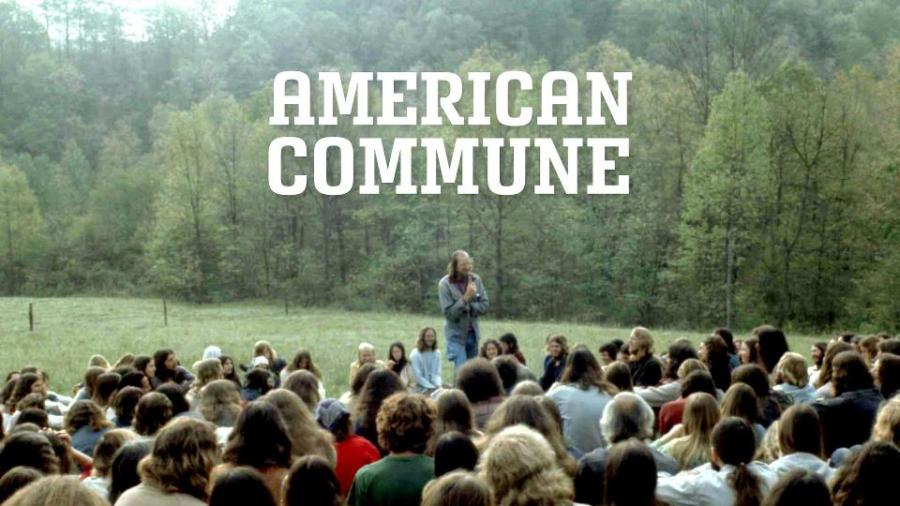

In April I visited one of the most famous communes in the world, The Farm in Lewis County, Tennessee. The Farm was supposed to be the epicenter of the summer of love, the epitome of ‘hippie’ freedom. On my visit I found something very different.

For background search “The Farm (Tennessee)” and it will be the first link (TheFarm.org). I cannot embed their website, but I can embed the wikipedia entry that mostly encapsulates the aura of the community: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Farm_(Tennessee).

A Fading Vestige of Freedom

As we rolled through the large gate separating the decaying rural town from the Farm, the once bustling commune stood silent, seemingly frozen. The commune that was born of one of the most ‘freeing’ and ‘enlightened’ movements America had to offer, was deathly quiet, and lacked the sunshine and joy from which it was forged. As the bus rolled down the paved road, rattling over the speedbumps, the illusion of The Farm began to fade, and its reality set in. The Farm–like its residents–has aged and softened with time. The former commune has dissolved from a communistic and possessionless existence into something far, far different.

On the Farm there is a curious mix of living, as if the commune itself has been gentrified. Interspersed with tiny houses, trailers, and run down houses are massive, remade, nearly suburban homes. These homes are used for continued communal living, but also have been renovated for guests to stay as Air BnB’s. A house on the Farm being used as an AirBnB means that not only are the houses now safe, mandated structures (unlike the fondly remembered past), but also are being used to produce legitimate revenue, something that would not be found in the origin of the Farm.

The Farm’s revenue is something that has not always been consistent. Today, it still seems as if there is a moderate revenue that comes from the Farm’s various “industries” such as: a publishing company, their midwifery practice, the mass production of soy, a mushroom growing kit producer, mediation practices, video production, part manufacturing, and a few other diverse ventures. Yet, in today’s age the publication industry is dying, and soy is no longer a novelty, thus the companies are no longer the bustling sources of income they once were, now just enough to keep the commune alive. The Farm once used this revenue to actively leave their plot of land and venture into other communities, but now their focus appears to be more landbound as the members have aged, and U.S. regulations have tightened.

As the bus came to a halt and we all trickled out onto a small decaying blacktop, our host was made clear. Before the group stood a man who could only be described as average. Douglas Stevenson, our host, had no ponytail, bright tie-dye shirt, or thick, circular glasses. Douglas’ clothes were not exactly normal, but nothing I–a native of San Francisco–did not see on a daily basis. Douglas carried himself proudly, but he did not ooze the chilled charisma typical to the perceived “hippie.”

Douglas instantly directed all the members of the tour into a circle, and grasped the hands of those beside him. The Farm’s tour began there, with our hands locked on a cracked blacktop. The only other object on the court was a small tricycle staring from the corner, tipped helplessly onto its side. A gentle breeze blew, accompanied by the occasional haunting creek but otherwise the only opposition to Douglas’ slow, methodical voice, was an ominous silence.

After hands were released, and the circle disbanded, the group was led into a very typical building. In the building a small presentation and a few made tables were awaiting us. Douglas began the presentation with an overview of the Farm. He was a skilled speaker, and his presentation was thorough. Yet, Douglas lacked the aura– the raw emotional magnetism–that must have been pivotal in creating the Farm.

Douglas went into depth about “the change.” “The change” happened in the late 70’s as the Farm began to be called on for their loans, and money became a necessity in order to keep the land. Douglas’s terminology regarding this shift in economic thought was particularly striking, and awkward. Suddenly the Farm went from a carefree society, to one that required distinct economic contributions. In the presentation this idea was a bit glossed over, except for the fact that following “the change” numbers on the Farm fell from 1200 to 200 in the matter of a few years. A fact that seemed to signify that the Farm had essentially collapsed, but Douglass carried on nonetheless.

“The Change” represents a lot of what was epitomized on the tour: the Farm no longer exists by the tenants from which it was allegedly founded. As Douglas explained, he was on site as the founding members of the Farm went and salvaged the wood, brick, and roofing that would eventually serve as the base of their community. Douglas beamed with pride as he spoke about the days they had to scrape together houses from abandoned buildings, and that they even perfected the art of transporting entire structures. The main schoolhouse and the dilapidated post office were two stoic reminders of the desperate ingenuity of the once thriving community.

Yet, upon seeing Douglas’s house later in the tour, with Priuses parked in front, and satellite dishes stoutly standing off the side, it was clear that some people of the community lived a life wildly different than that of the past. In going with this trend Douglas went to great length to mention that the farm had its own functioning private school that even attracted some neighboring children, but he quickly mentioned that none of his children attended said school.

The people of the Farm are, obviously, older now than they once were. With this age has come a clear shift in the style of living on the Farm. Douglas said that they do not actively invite older members into their communities because, “who would take care of them?” He continued to stress that this is not a vacation/retirement community, even as he admitted some people do just have secondary homes on the Farm. Douglas mentioned that many people were taking part in their trial periods but admitted that not a high percentage were deciding to join the community full time. The trial periods are supposedly an experimental time with the Farm, but a lot of the language surrounding these trial periods made it clear that the trial was as much for acceptance to the community than for acceptance of the community.

With this lack of new blood, the aging community appears to be slowly dwindling in numbers, while still attempting to maintain their founding values, and continuing the outreach programs that were tenants of the dissolving community. The Farm was founded on poverty, community, and most of all peace. As Douglas dove into the complex process for settling arguments (the most of which he described as rather petty), the continuation of peace felt more oppressive than progressive. The only tenant left then with the size of the community shrinking is the vow of poverty, which upon seeing Douglas’ impressive, nearly suburban house, became laughable.

Douglas ran us through the pillars of the Farm rather quickly, dancing around something that seemed to be laying at the center of it all: religion. Religion was a theme of the summer of love; but, the religion typical of the era was not singular and invited all beliefs. The Farm claimed to do the very same, mentioning that its foundations were built off of five major religions. However, these principles seemed to be specifically Christian principles, and Douglas even went so far as to call every baby born there as, “a baby like Christ.” This verbiage was extremely jarring given the supposed mixing of religions that was meant to occur, yet it seemed as if one religion was far more represented than the rest. Even in the slideshow that presented the tenants of the community, Mary and Christ were given their own slide: two beings standing above the rest, that were supposedly equal.

The lack of religious equality should not have been as shocking as it was to me. Douglas admitted that the majority of the Farm was white, and notably middle class in origin. Thus, it is clear that the majority of the Farm was likely raised in a Christian community, and despite their rebellion they had not abandoned every ounce of their upbringing. Still, though, it took me by surprise to see such a clear favoring of a single belief.

The religious orientation concluded with a rushed and rather chilling mentioning of doomsday preparation. Douglas pulled an image of a person in a gas mask, and quickly sped through a small speech about the idea of a doomsday. Quickly, he dove into his own form of doomsday preparation, which involved cultivating enough beans for him to sustain himself. He was able to do it, but it was far too much work to keep up with just to produce around “55 dollar’s worth of beans.” Douglas’s talks of the doomsday were spurred by references to “the banksters” and other societal norms that he, and the Farm, had completely vilified.

Ultimately, Douglas kept the moment light, but he punctuated the final thought by saying, “I know I can do it, need be,” and moved on to talk of the land itself. Douglas lost me when he mentioned a potential doomsday, but a passion, a missing charisma, was imbued into his voice as he began to speak on the next topic: the Farm’s belief in the spirituality of nature.

Douglas said there was something very spiritually rewarding about farming from your own land, and while one could be skeptical, his confidence was intoxicating. This belief overshadowed some of what he had said about religion. Backtracking on formal religion he spoke about the spirituality of nature and the merits of connecting with the land. This moment was followed with the serving of some of the Farm’s own food.

As I sat staring out at a metal fence and a rusted swing-set, I ate a Soy pot-pie that was virtually indistinguishable from chicken. I was taken aback by the freshness of the yams, and the general incredible taste derived from organic ingredients and a small kitchen. As I ate the food, the aspect of spirituality that Douglas mentioned felt a little more plausible, and the alluring aura of communal and spiritual living that the Farm presented felt a little more tangible, and for a moment, I understood what drew each of these aging souls to the farm in the first place. Even as the Farm is decaying and drifting from its origin, the food holds a tether to the magic that was the summer of 1969.